All the analysed herbal teas had pH between 6.9 and 7.4 (Table 1). The lowest pH values were determined in Cistus incanus herbal tea (6.9), followed by Camellia sinensis herbal tea (7.0). The highest pH values noted in our study (7.4) were determined in Centaurium erythraea Rafn and Leonurus cardiaca herbal tea.

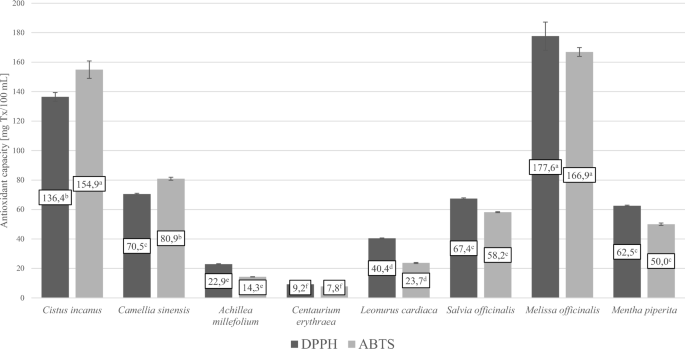

Next, the antioxidant properties of all the tested herbal teas were determined (Table 1, Fig. 1). The antioxidant capacity (DPPH assay) was the highest for lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) herbal tea (177.6 ± 9.6 mg Tx/100 mL). A statistically significantly (p ≤ 0.05) lower value was determined for Cistus incanus herbal tea (136.4 ± 3.0 mg Tx/100 mL). Even lower antioxidant capacities (from 62.5 ± 0.5 to 70.5 ± 0.5 mg Tx/100 mL) were found in Camellia sinensis, Salvia officinalis and Mentha piperita teas. Achillea millefolium and Centaurium erythraea teas had the lowest antioxidant capacity, 22.9 ± 0.3 and 9.2 ± 0.1 mg Tx/100 mL, respectively. The antioxidant capacity measured with the ABTS method confirmed the results obtained with the DPPH method. In this assay, we also found the highest antioxidant capacity of teas from Melissa officinalis and Cistus incanus, 166.9 ± 3.0 and 154.9 ± 5.9 mg Tx/100 mL respectively. In the ABTS method, the lowest values were obtained by Centaurium erythraea, Achillea millefolium and Leonurus cardiaca teas (from 7.8 ± 0.1 to 23.7 ± 0.4 mg Tx/100 mL).

Antioxidant capacity of the analysed herbal teas. DPPH, Antioxidant capacity; ABTS antioxidant capacity. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA using the Tukey’s post hoc test: different letters in data columns (DPPH or ABTS) indicate statistical significance (p ≤ 0.05).

Herbal teas with the highest antioxidant capacities (determined in DPPH and ABTS assays) had the highest content of total polyphenols determined by the Folin-Ciocalteu method (Table 1). Melissa officinalis herbal tea had statistically significantly the highest total polyphenol content (252.3 ± 7.4 mg GAE/100 mL). Cistus incanus tea also had a relatively high polyphenol content (177.7 ± 3.2 mg GAE/100 mL). Salvia officinalis, Mentha piperita and Camellia sinensis teas had a lower polyphenol content (Table 1). On the other hand, in the second method used to determine the total polyphenol content (FBBB assay), teas from Cistus incanus and Camellia sinensis gave the highest values. Melissa officinalis had a slightly lower polyphenol content than teas from Cistus incanus and green tea. In this stage of the study, as with the DPPH method, the lowest amounts of polyphenols were determined in teas from Centaurium erythraea and Achillea millefolium—1.3 ± 0.1 and 7.7 ± 0.2 mg GAE/100 mL. In our study, Melissa officinalis tea had the highest total flavonoid content of all the teas analysed (Table 1). This coincided with the results mentioned above, in which we reported the highest antioxidant capacity and total polyphenol content of lemon balm tea. Teas from Salvia officinalis and Mentha piperita had a relatively high total flavonoid content. The other herbal teas had more non-flavonoid polyphenols.

The high antioxidant properties of lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) were also pointed out by other researchers. Gorjanović et al.30 found the highest total polyphenol content in lemon balm tea and black tea, and a low content in yarrow tea. In that study, green tea had a slightly higher total polyphenol content than in our study (81.9 vs. 65.3 mg GAE/100 mL). Furthermore, lemon balm tea had a higher total polyphenol content than green tea30, which was in line with our results. In addition to lemon balm tea, we showed that Cistus incanus tea also had high antioxidant properties. It had high antioxidant capacity and high total polyphenol content. Many studies have reported that aqueous infusions prepared from Cistus incanus leaves are considered to be a source of polyphenols, not only flavonoids, but also proanthocyanidins, ellagitannins and phenolic acid31,32. This would explain a rather high content of non-flavonoid polyphenols in Cistus incanus infusions. This is also pointed out by Bernacka et al.18, who detected a rather high content of non-flavonoid polyphenols (TPC-TF) in analysed Cistus incanus infusions. In that study, the total polyphenol content of infusions of Cistus incanus from Greece, Albania, or Turkey was similar18. However, in another study, the different Cistus incanus extracts from Greece, Turkey and Albania analysed had different values for the total polyphenol content (range 14–623 mg/g d.w.), with Cistus incanus extracts from Greece achieving the highest values33. We also observed high polyphenol content (in the FBBB assay) in Camellia sinsnesis tea and Salvia officinalis tea (in the Folin-Ciocalteu TP assay). Evidence from several studies suggests that Salvia officinalis has strong antioxidant properties and counteracts oxidative stress13, although the results of the total polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity were lower than lemon balm and green tea30. We found the lowest antioxidant properties (lowest total polyphenol content and lowest antioxidant capacity) in tea from Centaurium erythraea. The low antioxidant capacity of the Centaurium erythraea is confirmed by other studies. Šiler et al.34 showed that secoiridoides contained in C. erythraea lack antioxidant activity. Xanthones may be responsible for the minor antioxidant properties of this plant. These compounds have hydroxyl groups in their structure that can easily provide electrons and quench the DPPH radical9. In our work, the total polyphenol content and antioxidant capacity of Achillea millefolium tea was also relatively low compared to other herbal teas. In the study by Dias et al.35, the total polyphenol content and total flavonoid content in Achillea millefolium infusions were higher. In contrast, Salomon et al.36 found significantly lower antioxidant properties of Achillea millefolium compared to Achillea atrata.

Our study showed a high correlation between total polyphenol content (the Folin-Ciocalteu method) and antioxidant capacity in both the DPPH (0.994) and ABTS (0.967) assays (Table 2). Gorjanović et al.30 showed a lower correlation of 0.811 and 0.618, respectively. We determined a high correlation between DPPH and ABTS assays (0.981), while Gorjanović et al.30 obtained a relatively low correlation (0.690). Another study found a strong positive correlation between DPPH and TP (~ 0.99) and moderate correlation with FBBB, TF (~ 0.8). Furthermore, these studies showed a high correlation between DPPH and ABTS (~ 0.98)33.

We have also seen a moderate correlation between the TP and FBBB methods (0.748). This was due the differences in both methods. In our study we noted that the results on the total polyphenol content was higher according to the FBBB method than obtained with the Folin-Ciocalteu assay, but only in the case of Cistus incanus tea and Camellia sinensis tea. This was similar to earlier observations, but it was about other products37,38,39. Similar or lower polyphenol content values in the FBBB method in the other teas analyzed can be explained by the presence of other bioactive compounds and differences in the selectivity of these methods. The FBBB method, developed by Medina, is less popular than the TP method, but it is more specific to phenols and less affected by other interfering compounds. Major disadvantage of the Folin-Ciocalteu assay is that the reagent reacts with reducing substances and measures the total reducing capacity of a sample rather than of the phenolic compounds37,38,39. It has been shown that not only phenols, but also other compounds (e.g. certain vitamins, sugars, proteins, and thiols) can react with the Folin-Ciocalteu reagent, confirming the weaker specificity of this method40. Both methods (TP and FBBB) were further investigated for their susceptibility to interference in different (plant) matrices. Folin–Ciocalteu assay showed interferences for 75% of the flours (attributed to reducing sugars and enediols), whereas FBBB only for legumes and nuts (attributed to the presence of tyrosine). Both methods presented excellent reproducibility, but FBBB displayed 1.5 times higher sensitivity41. Despite its known interferences, Folin–Ciocalteu assay is still widely employed in different matrices42. Recently, a high correlation between the FBBB method for determining polyphenols and the HPLC–UV method in olive oil has also been demonstrated43.

Antibacterial activity of herbal teas

The analysed infusions demonstrated varied antimicrobial activity. Such differences are also indicated by the findings achieved by other researchers, who investigated the antimicrobial activity of various herbal infusions, including aqueous, ethanol and methanol ones44,45. In our experiment, we tested aqueous extracts (teas) from common herbs: mint (Mentha piperita), sage (Salvia officinalis), lemon balm (Melisa officinalis) and green tea (Camelia sinensis), as well as well less popular ones, but all with pro-health potential, such as cistus (Cistus incanus), yarrow (Achillea millefolium), common centuary (Centaurium erythraea Rafn) and motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca). The results of the antimicrobial activity determined in the tested infusions equivocally indicate that two of the herbs did not have such an effect on any of the tested bacterial strains. These were infusions from yarrow (Achillea millefolium) and common centuary (Centaurium erythraea) (Tables 3 and 4). Also, the infusion from motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) showed very low antimicrobial potential. This means that 25% of the tested infusions did not demonstrate any antimicrobial potential. In their work, Hacioglu et al.45 revealed a lack of antimicrobial activity of some of the teas they tested. More specifically, out of 31 herbal infusions submitted to tests, 15 were shown to demonstrate antimicrobial activity, meaning that 52% of the tested herbal teas did not inhibit the growth of the tested microbial strains.

The available research papers dealing with the antimicrobial activity of yarrow (Achillea millefolium) deliver the findings that confirm it, unlike our results. However, the microbial activity of this herb was not analysed in aqueous infusions. Grigore et al.46 proved the antimicrobial activity against the Gram-positive bacteria (S. aureus), Gram-negative bacteria (including Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa) and fungi, including Candida albicans, produced by different extracts of yarrow (Achillea millefolium), such as hydroalcoholic, hexane, and methanol ones. Similar extracts were studied by Karaalp et al.47, who demonstrated the antimicrobial activity of the analysed yarrow (Achillea millefolium) extracts against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, where the effect on Gram-positive bacteria (Bacillus cereus, Enterococcus faecalis and Staphylococcus aureus) was stronger than on Escherichia coli. A slightly stronger activity of the analysed infusions against strains of Gram-positive bacteria was also demonstrated in our study (Table 3). The growth of only two strains from this group, Listeria inocua L1001 and Clostridium perfringens Clpe0001, was not inhibited by any of the infusions submitted to our study. As for Gram-negative bacteria, only two infusions, from cistus (Cistus incanus) and green tea (Camelia sinensis), showed antimicrobial activity against most of the tested strains (Table 4). In this group of bacteria, similarly to Gram-positive bacteria, none of the infusions inhibited the growth of two tested strains. These were Escherichia coli 31 and Salmonella Enteritidis. The other strains of the genus Escherichia coli and the remaining serotypes of Salmonella sp. rods were inhibited by the mentioned infusions. These results substantiate the assumption that the sensitivity of bacteria to herbal infusions, same as to other environmental factors, is a strain-related trait. When analysing the research results, we could conclude that infusions of lemon balm (Melisa officinalis) and peppermint (Mentha piperita) showed antimicrobial activity only towards Gram-positive bacteria, and a much higher activity was noted against spherical bacteria (Table 3). Infusions from peppermint (Mentha piperita) and lemon balm (Melisa officinalis) inhibited the growth of all tested strains of S. aureus and some strains of E. faecalis. Additionally, in comparison to Mentha piperita, lemon balm tea inhibited the growth of one of the two tested strains of Bacillus cereus. In turn, tea from sage (Salvia officinalis) showed inhibitory activity against two of the twelve Gram-positive strains put to tests (Table 3).

Abdei-Naime et al.15 demonstrated the inhibitory effect of Melisa officinalis on strains Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, whereas no antimicrobial effect on Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae was confirmed15. These results are comparable to our findings, except the Gram-negative bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which were not affected by Melissa officinalis infusion. Several authors pointed that Melissa officinalis is a plant which is rich in polyphenolic compounds, but the extraction method and the solvent used play a significant role48,49.

In a review paper dedicated to the antimicrobial activity of lemon balm (Melisa officinalis) and the plant’s potential as a food preservative, Carvalho et al.50 cite numerous examples of the antimicrobial effects of this herb against bacteria, fungi and viruses. However, it needs to be mentioned that essential oils demonstrate a much higher activity than other plant extracts. When analysing the research results quoted in the above article50, it emerges that particular herbs show highly varied antimicrobial effects against tested strains of microbes, which has also been noted in our study. Recent studies have shown that this plant, through various mechanisms, can also fight viruses, including Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)51.

As regards Mentha piperita, similarly to our findings, Bardaweel et al.52 report its moderate antioxidant effect and weak antimicrobial activity. The inhibitory effect of Mentha piperita against S. aureus has been confirmed by others53. In another study, on the antibacterial activity of peppermint oil and different peppermint extracts, Singh et al.54 found that the highest inhibitory activity against the indicator strains was demonstrated by essential oils as well as ether, chloroform and acetate extracts of peppermint. Distinctly lower activity was determined in aqueous and ethanol extracts. Same as in our experiment, the cited authors concluded that S. aureus was most sensitive to the tested substances, while Gram-negative E. coli rods were the least sensitive ones54. Interesting results regarding peppermint (Mentha piperita) extracts were obtained by Faris Shalayel et al.55, who concluded that peppermint extracts showed antimicrobial activity against pathogenic bacteria, including MRSA (Methicillin-resistant S. aureus) and MRSE (Methicillin-resistant S. epidermidis) strains55.

Sage (Salvia officinalis) tea was characterized by lower antimicrobial activity than teas made of Mentha piperita and Melisa officinalis, as it only showed antimicrobial effects on two of the three tested strains of S. aureus. Garcia et al.56 also demonstrated an effective antimicrobial activity against the strain S. aureus and a lack of such an effect on Streptococcus agalactiae, Candida albicans and Candida tropicalis. The authors concluded that Salvia officinalis L. could contribute to the inhibition of pathogens in the skin microbiota56.

The infusion from motherwort (Leonurus cardiaca) showed antimicrobial activity only towards one tested strain, S. aureus 2G (Table 3). Micota et al.57 also demonstrated its activity against S. aureus.

The minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for each infusion was determined to be at a level of 7.5% (v/v) for Gram-positive strains 10% (v/v) for Gram-negative bacteria (Table 5). In this case, also Camellia sinensis and Cistus incanus teas were the most effective towards a wide range of microorganisms.

To summarise, it should be underlined that the highest antimicrobial potential against the tested strains was demonstrated by two infusions, of Cistus incanus and Camellia sinensis. They were the only infusions that inhibited the growth of Gram-negative bacteria, and the increased resistance of Gram-negative, and the greater resistance of Gram-negative bacteria to the analysed infusions could be attributed to the presence of lipopolysaccharides in their outer membrane, which improve the resistance to antimicrobial factors. Furthermore, Cistus incanus and Camellia sinensis teas, along with Melissa officinalis tea, had the highest polyphenol content and the highest antioxidant capacity. These samples also had the highest efficacy against Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains, with the exception of Melissa officinalis, which showed inhibitory abilities only against Gram-positive strains, which have a thinner cell wall and are more susceptible to the effects of polyphenols.

The capability of green tea to inhibit food-borne pathogens, including E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella typhimurium, Listeria monocytogenes was first indicated by Hamilton-Miller58. However, it is unclear which green tea ingredients act as main antibacterial agents, and which bacteria are most strongly inhibited. This gap in knowledge is implicated in a review paper by Zhao et al. 6. It has been determined that epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) has the highest antibacterial activity, exerting the most significant effect on S. aureus6. However, there is a lack of research focusing on this question. Our study therefore provides a broader view of the antibacterial properties of green tea and other herbal infusions towards as many as 22 Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains.

With respect to cistus (Cistus incanus), the antimicrobial activity of its essential oils, which demonstrate high potential, is studied more often59. In one of few studies including a commercial hydroalcoholic extract of Cistus incanus, it was determined that Staphylococcus aureus was more sensitive than Escherichia coli to the tested substance60. The results obtained in our experiment reveal antimicrobial potential of cistus (Cistus incanus) infusions, which was characterised by a high content of polyphenols and high antioxidant capacity.

link